Eight Ways J.P. Morgan Defined the Good Life

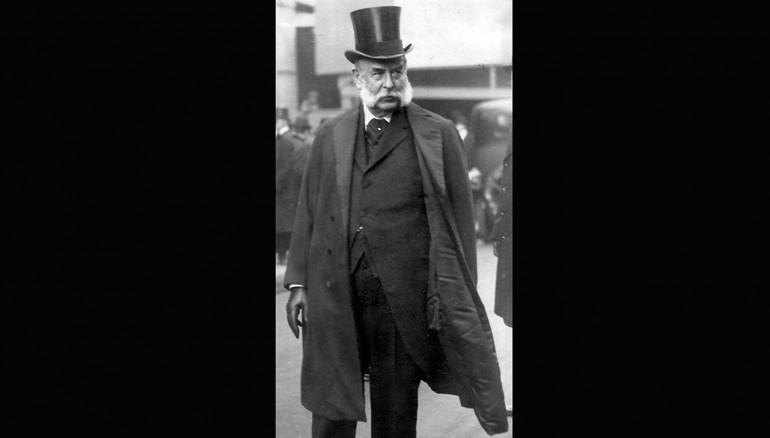

Still gleaming from the Gilded Age well into the early 1900s, a handful of capitalists came to symbolize success in the United States—branded both as benevolent philanthropists by admirers and robber barons by critics. But among the financial titans at the turn of the 20th century, one person sat at the pinnacle of power, prominence, and almost unfathomable wealth—John Pierpont Morgan.

Reigning over American aristocracy until his death in 1913, the intimidating tycoon was a visionary when it came to business. A builder of industry and infrastructure, he even bailed out the Federal Reserve at one point. Morgan’s fiscal acumen fueled his affluence exponentially, and he took luxury to the next level.

With insights provided in the biography Morgan: American Financier by Jean Strouse and assistance from the Pierpont Morgan Library, here are the ways the man enjoyed the money he amassed.

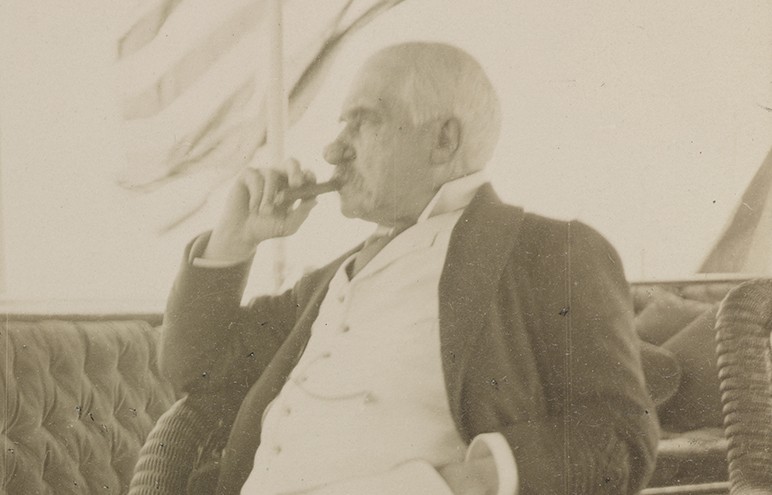

Yachts

To escape the often tempestuous financial scene, J.P. Morgan found solace on the sea and owned a series of yachts during the course of his lifetime. It is Morgan who, when asked the expense in maintaining such a vessel, is credited as saying the now cliché approximation of, “if you have to ask how much it costs, you can’t afford it.”

Commodore of the New York Yacht Club from 1897 to 1899, Morgan purchased his first luxury craft in 1881, a 185-foot steam sailor christened Corsair. Just nine years later, Morgan commissioned the 241-foot Corsair II (designed by John Beaver-Webb and built by Neafie & Leavy out of Philadelphia), which included a 30-foot tender.

A haven from the public eye, the yacht was a pelagic playground for an elite few. Included among the onboard opulence was handmade bone china by Minton, Tiffany cigar-cutters, and a set of poker chips carved from ivory. The latter sold for $66,000 at auction in 2011.

In 1898, the Corsair II was conscripted into service by the United States Navy and became the USS Gloucester, a gunboat used during the Spanish-American War. This naturally necessitated that Morgan have a replacement, so the 304-foot Corsair III was constructed the same year by T.S. Marvel Shipbuilding. Amidst the yacht’s lavish layout were found a library that extended across the beam, a player piano, cases of wine and brandy, humidors stocked with Cuban cigars, and a comprehensive collection of dining accessories, including pearl-handled fruit knives, julep strainers, finger bowls and, of course, asparagus tongs. After Morgan’s death, the third iteration of Corsair saw action as a patrol ship in WWI and as a survey ship in the Pacific theater during WWII.

Sharing his father’s nautical nature, J.P. Morgan Jr. carried on the tradition by having the 343-foot Corsair IV completed in 1930. The largest yacht built in the United States at the time, it came at a cost of $60 million by today’s standards.

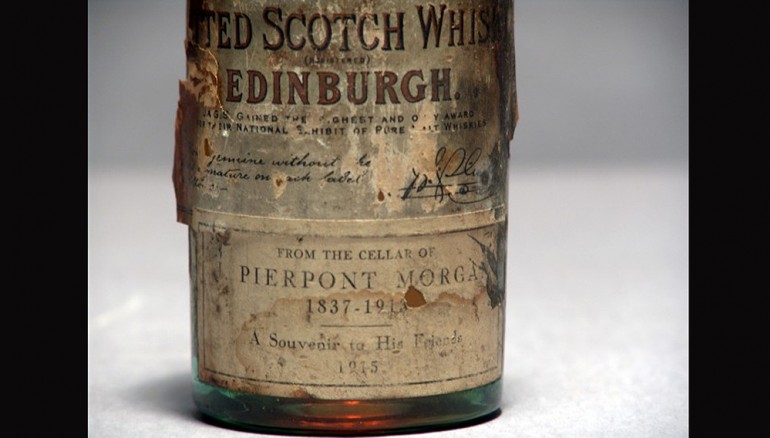

Wine and Spirits

A man known to throw down a few belts with the best of them, Morgan’s appreciation for libation was bullish, beginning with his ritual rye Manhattan at the end of every trading day. The magnate was also partial to old Madeira wines from Portugal, perhaps savoring the sweet citrus and caramel notes of a 1780 Borges Bual vintage or hints of hazelnut in an 1825 Leacock Madeira Seco during a game of high-stakes poker with his prominent pals.

The same vision for risky conglomeration that made him an icon in industry may have led to the supposed creation of his own bold beverage, the Alamagoozlum. With Morgan cited as the source in Charles Baker’s cocktail primer, The Gentleman’s Companion: The Exotic Drinking Book (1939), the recipe calls for: gin, Jamaican rum, Chartreuse liqueur, gomme syrup, orange curaçao, Angostura bitters, and egg whites—a labor-intensive inebriate that he probably had the housemaid mix.

But nothing symbolizes the good old boys club and back-room deals like smoky whiskey, and J&G Stewart Scotch was one of Morgan’s desired drams. In 2011, a bottle of the prized spirit from his cellar sold for $7,500 at auction.

Residences

Referring to high society’s residences during the latter part of the 1800s, Morgan biographer Jean Strouse writes, “The houses of the Gilded Age served as domestic museums—private exhibitions of architecture, artifact, and art that would testify to their owner’s ample means and stylish tastes.” A man to the manor born, Morgan certainly made sure his many mansions and country estates were structured statements of prosperity.

Nowhere was this more apparent than his primary place at 219 Madison Avenue in New York. In 1882, the family moved in to the massive brownstone and festooned it with fine art, stained-glass domes and skylights, and Oriental rugs. With the interior design detailed by furniture maker Christian Herter, the home featured a red-columned drawing room, a gentleman’s library with raised fireplace, a 60-foot-long conservatory, and a marble-columned dining room on the main floor alone. And it was also the first home in the city to be exclusively lit by Thomas Edison’s newly introduced invention, the lightbulb.

The fact that Morgan was not an outdoorsman and did not particularly enjoy the country did not stop him from possessing rural retreats. In 1872, he bought the Cragston estate in Highland Falls, N.Y. At the time, it included a farmhouse, several outbuildings, stables, kennels, and a lake. By 1886 he had extended the property to 675 acres and hired architects Peabody & Stearns to turn it into a three-story provincial palace with multiple wings, a piazza, a library, and a wine cellar.

Adding to his list of luxury lairs that included those in Glen Cove, N.Y.; Newport, R.I.; Jekyll Island, Ga.; and two adjacent townhouses in London (where he kept the majority of his fine-art collection), Morgan bought a tony homestead in the Adirondack Mountains in the 1890s. Named Camp Uncas by its former owner, the property consisted of 1,500 acres that included an iron foundry, a sugarhouse, and log cabins. Morgan equipped the main lodge with modern bathrooms, a kitchen, beds with horsehair mattresses, and two Steinway pianos. Also on hand were a team of carpenters, stable hands, farmers, landscapers, and house staff. After building an access road, Morgan and his neighbors also added an 18-mile rail line to ease accessibility. By 1899, he had a train steaming in place around the clock at the local station in the event that business called.

Automobiles

When it came to cars, the only marque for a man like Morgan was Rolls-Royce. While staying in London as part of his annual summer pilgrimage to Europe, the financier fancied a bespoke automobile and ordered a Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost—a vehicle the magazine Autocar had labeled “the best car in the world” in 1907. The 1912 model he ordered carried a straight-6 engine with 50 hp and a 3-speed manual transmission. It was delivered in the color claret by the spring of that year.

Morgan’s customized accoutrements included monogrammed doors, velvet carpeting, silk curtains, ubiquitous brass fittings, silver flower vases, mother-of-pearl trays, a Charles Frodsham & Co. clock, an electric cigar lighter, and hat racks. After seeing his refined, $7,275 ride, Morgan ordered two more just like it—one for use in New York and the other as a Christmas present to a friend.

Clothing

The Latin proverb “vestis virum facit” (clothes make the man) may have been a mantra of Morgan’s—one impressed upon him by his father Junius. For the latter, proper tailoring demanded a transatlantic crossing and a sartorial sojourn on London’s Savile Row.

A favorite stop was Henry Poole & Co., a haberdashery established in 1806 and clothier to royalty around the world, including King Edward VII. The younger Morgan was introduced into its fold of privileged clientele in 1857 and would be a regular customer for the rest of his life. Stateside, Savile Row’s reputation for exclusivity had grown to the point that false rumors circulated about Morgan being turned away by the tony tailors. Henry Poole & Co. eventually quelled the allegation by making public their ledger with the magnate’s moniker recorded. Bred to look the part, Morgan’s son, J.P. “Jack” Morgan Jr., continued a lifelong loyalty to the label.

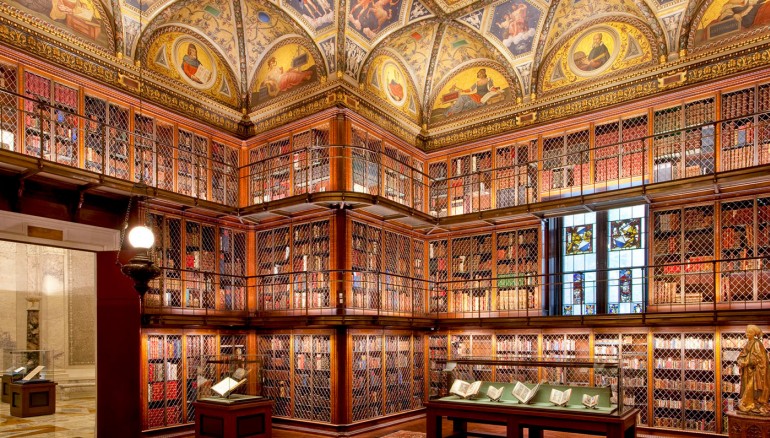

Collections: Books and Manuscripts

A bibliophile of the highest order, Morgan became such a rapacious collector of rare books and manuscripts that by 1902 he commissioned architect Charles Follen McKim to design a private library. Specializing in the Italian Renaissance aesthetic, McKim worked closely with Morgan throughout the four-year project. Built of Tennessee marble blocks, the $1.2 million temple to texts featured an interior of Roman marble floors, lapis lazuli columns, and bronze bookcases able to hold thousands of treasured tomes. In 1905, Morgan hired librarian Belle da Costa Greene in what may have been one of the best decisions of his life, as she proved invaluable in helping to oversee and grow the collection.

Morgan’s voluminous amount of books encompassed all categories, from religious to secular, and included the Lindau Gospels (a 9th-century collection of the Biblical accounts of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John for which he paid $50,000), three Gutenberg Bibles circa 1450s; a 66-volume set of Napoleon and His Generals; and the racy A Burlesque Translation of Homer from 1792. He also purchased the manuscripts for Life on the Mississippi and Pudd’nhead Wilson directly from author Mark Twain himself.

Morgan often found works with the assistance of London book dealers J. Pearson & Co. and Henry Sotheran & Co. but also grew his inventory by purchasing the collections of others, such as illuminated manuscripts and over 600 early books from the library of William Bennett of Manchester for $700,000. Included in the acquisition were 32 examples from the 15th-century printer William Caxton (owner of the first printing press in England) and an edition of Augustine’s City of God from 1486.

Also among Morgan’s manuscripts was the opening page of Book I from John Milton’s Paradise Lost (from 1665) and one of his most-prized literary possessions, the Farnese Book of Hours, completed by Rome’s Giulio Clovio in 1546 for cardinal Alessandro Farnese. The masterwork (with a gold-and-silver cover) was the primary piece in a $112,500 purchase made in 1903.

Gifted to the city by John Pierpont, Jr. in 1924, the Morgan Library & Museum complex remains on the original site and is open to the public.

Collections: Watches

Catalogue of the Collection of Watches—the Property of J. Pierpont Morgan compiled by G.C. Williamson.

John Pierpont Morgan’s appreciation for the finest craftsmanship combined with his appetite for acquisition naturally drew him to the horologic arts. His comprehensive assemblage covered European clockworks from the 1500s through 1800s, with a focus on those from the Renaissance.

Depth was provided by his purchase of collections that had belonged to German watch dealer Carl Heinrich Marfels and banker George Hilton Price, procured in 1909. Morgan paid $360,000 for the approximately 88 timepieces from Marfels alone. Among the assortment were a watch considered to be the most expensive in the world at the time (a Limoges-enameled horologe valued at $25,000) and one in the shape of a cross made by Anthoine Arland in 1550.

But these existing compilations were not his sole sources. On a five month trip through Europe in 1902, for example, Morgan picked up a rare piece in Paris—an 18th-century longcase regulator clock that portrayed Ovid’s story of Apollo on the case and highlighted the work of Balthazar Lieutaud, Ferdinand Berthoud, and Philippe Caffieri.

Wanting detailed documentation of the examples he owned, Morgan commissioned the book Catalogue of the Collection of Watches—the Property of J. Pierpont Morgan compiled by G.C. Williamson. Gilded and bound in crushed Morocco leather, one copy of the catalog was estimated to fetch up to roughly $26,000 at a Christie’s auction in 2012.

Collections: Fine Art

When it came to hunting down fine art, Morgan was the apex predator in the United States—the likes of whom would not be seen again until J. Paul Getty several decades later. And it was a passion that would only intensify as he grew older, evidenced by the fact that he spent about $60 million (the equivalent of $900 million in the present economy) on artwork during the last 20 years of his life.

“Morgan was fully caught up in a romance with art that combined his cultural nationalism, interest in history, sensuous response to beauty, and love of acquisition,” writes biographer Jean Strouse. “ Operating on an imperial scale in the early twentieth century, he seemed to want all the beautiful things in the world.”

Those “beautiful things” came in multiple mediums for the collector, including paintings and drawings from the Old Masters, portrait miniatures, porcelains, bronze sculpture, and photography. For the latter, Morgan helped finance noted photographer Edward S. Curtis on his mission to document the culture of Native Americans, one that was quickly vanishing from the landscape of the United States. Morgan’s terms for payback were to receive 25 sets of the planned 25-volume compendium (1,500 images) along with 500 original prints when the project was completed.

Among his now near-priceless paintings and miniatures were Portrait of Nicolaes Ruts, Rembrandt’s portrait of a merchant done in 1631 (purchased for $30,000), the Armada Jewel (a miniature profile of Elizabeth I set in a gold pendant and believed to have been given to the Queen after crushing the Spanish Armada), and Raphael’s The Colonna Altarpiece (later donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York).

After Morgan’s death, his son had the Metropolitan exhibit almost all of his father’s art collection (save for the Morgan Library’s inventory) the following year. A majority was later sold off or donated to museums around the world.

SOURCE: Robb Report

POSTED: MAY 31, 2016

AUTHOR: Viju Mathew